Les assureurs-incendie

Cent ans de service

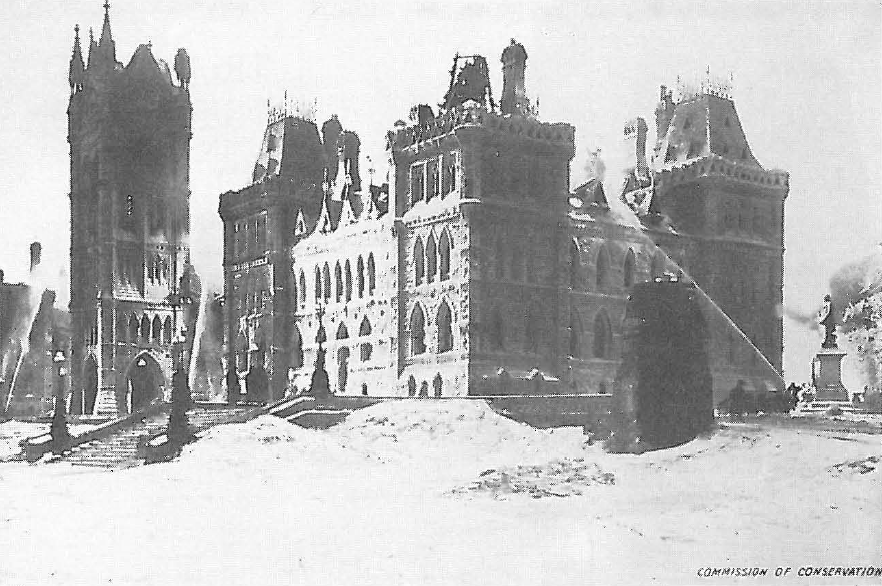

Le classement des localités à des fins d’assurance-incendie, le « Classification Standard for Public Fire Protection (CSPFP) » et le Service d’inspection des assureurs incendie (SIAI) remontent à plus d’une centaine d’années, à une époque où de violents incendies détruisaient des secteurs complets des villes canadiennes et américaines. De grands incendies, tels ceux de Portland (1866), de Chicago (1871) et de Toronto (1904), et l’incendie consécutif au tremblement de terre de 1906 à San Francisco ainsi que les incendies subséquents ont fait ressortir la vulnérabilité des villes à ce fléau. A cette époque, l’aménagement des ressources en eau et les codes et services d’incendie n’en étaient alors qu’à leurs débuts et n’étaient tout simplement pas suffisants pour prévenir ou maîtriser les feux dévastateurs. Le nombre de sinistres était phénoménal et menaçait sérieusement la solidité financière de l’industrie des assurances.

Devant l’énormité du problème, le National Board of Fire Underwriters des États-Unis a chargé une équipe technique de se pencher sur la situation des grandes villes en matière d’incendie. Au Canada, la Canadian Fire Underwriters » Association s’est vu confier une mission semblable et des techniciens ont évalué le risque d’incendie de nombreuses villes. et des techniciens ont évalué le risque d’incendie de nombreuses villes.

La citation qui suit est tirée du livre de Christopher L. Hives, « The Underwriters: the history of the Insurers’ Advisory Organization and its predecessors, the Canadian Fire Underwriters' Association and the Canadian Underwriters' Association », publié en 1985.

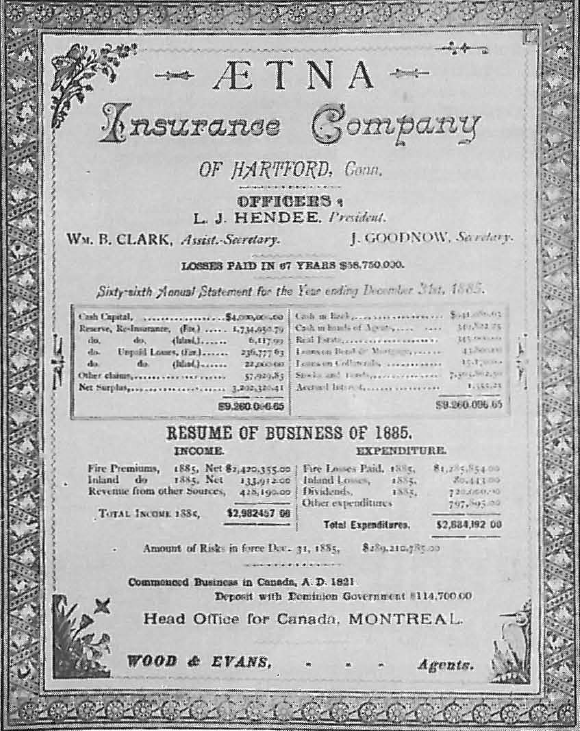

« La fréquence élevée des grands incendies au 19e siècle dans les villes canadiennes a eu pour conséquence de mener à la faillite de nombreux assureurs incendie. Pour venir en aide à l’industrie en difficulté, le nouveau gouvernement canadien a adopté la loi intitulée Insurance Company Act en 1868. »

Au fil des années, les « Canadian Underwriters' associations », provinciales ou nationales, étaient connues du public simplement comme « The Underwriters » (les assureurs-incendie), et des personnes dans l’industrie comme « The Board » (le Conseil)

Lire l’histoire complète (Avertissement : Le document est volumineux. 32mb)

1666 - The Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of 1666 was a catastrophic event that burned for 4 days, consumed 436 acres of the city, and 13,200 houses. The fire was only stopped by destroying buildings in the way of the fire to prevent further spreading. As a result Dr. Nicholas Barbon,a physician and leading builder, proposed the idea of distributing the losses incurred during a fire among a larger group of people. Heeding the harsh lesson imposed on them by the fire, many customers flocked to his firm, known as "The Fire Office", to take advantage of his new service.

Similarly, the New York fire of 1835 caused over $15 million in damages and bankrupted the city’s insurance companies, causing companies to define risk more clearly and to recognize the necessity of improving their financial stability. In 1866, the leading American companies formed the National Board of Underwriters in an effort to introduce some uniformity into the industry. The organization assumed a scientific approach toward the classification of risks and granted local representatives more duties to carry out closer inspections of the important risks. Fire maps came into use at this time.

Read more on Chapter 1

The Formation & and the Early Years of the CFUA (1883-1900)

The Great Fire of 1666 was a catastrophic event that burned for 4 days, consumed 436 acres of the city, and 13,200 houses. The fire was only stopped by destroying buildings in the way of the fire to prevent further spreading. As a result Dr. Nicholas Barbon,a physician and leading builder, proposed the idea of distributing the losses incurred during a fire among a larger group of people. Heeding the harsh lesson imposed on them by the fire, many customers flocked to his firm, known as "The Fire Office", to take advantage of his new service.

Similarly, the New York fire of 1835 caused over $15 million in damages and bankrupted the city’s insurance companies, causing companies to define risk more clearly and to recognize the necessity of improving their financial stability. In 1866, the leading American companies formed the National Board of Underwriters in an effort to introduce some uniformity into the industry. The organization assumed a scientific approach toward the classification of risks and granted local representatives more duties to carry out closer inspections of the important risks. Fire maps came into use at this time.

Read more on Chapter 2

Growing Pains (1900-1910)

Fire losses rose from $3,905,000 in 1891 to $4,701,000 by 1897. This figure almost doubled in 1900, when losses reached $7,774,000, exhausting an astonishing 93.31 percent of the total revenues collected. Despite the CFUA’s best efforts in encouraging municipalities to increase firefighting equipment, its suggestions often fell on deaf ears. As a last resort, the association increased the rates charged to cities that failed to act on its recommendations.

In response to the problems arising out of the outmoded system. the Canadian Fire Underwriters' Association decided to move toward a more exacting. scientific form of rating. In 1901. the association decided to employ specific

Read more on Chapter 3

Trials and Tribulations (1910-1920)

Between 1910 and 1920, the CFUA reached a level of maturity that allowed for changes to the organization without jeopardizing its existence. For several years the association had attempted to reach an agreement with the Goad Company for use of its fire insurance plans but after many negotiations the CFUA decided the association should produce its own insurance plans in December 1910. The proposed Plans Department would engage a surveyor and assistants as required, and sell its own plans at cost to member companies. In the years following, the CFUA decided to partner with the Goad Company for only 5 years, eventually leading to the CFUA buying out the Goad Company including all the insurance plans. During this time the Plans Department also become the Underwriters’ Survey Bureau.

Read more on Chapter 4

Growth and Prosperity (1920-1930)

At the outset of the 1920s, the association renewed its effort to eliminate the rate and rule infractions which had prevented the smooth operation of the organization. Non-tariff competition was discouraging, but rate cutting and other unfair competition among members themselves was a much more serious matter.

At the 40th annual meeting in 1923, President Alfred Wright assessed the situation: "In the past our anxieties have mainly arisen from without, and all have been successfully surmounted, but now our principal difficulties are from within." Following this meeting, stamping become the new standard which indirectly highlighted a considerable volume of business written by member companies without regard for tariff rates and rules.

Read more on Chapter 5

The “Hungry” Thirties (1930-1940)

Premiums fell rapidly from $27,626,057 in 1929 to $19,396,000 in 1933. The CFUA economized in a number of areas. One measure taken was a five percent reduction in the salaries of the association staff. This was a moderate drop relative to business returns, and not as bad as it seemed, considering the cost of living had also fallen.

The Canadian Fire Underwriters' Association also suffered during the depression. Before the decade ended, CFUA would be dissolved and amalgamated with automobile and casualty associations to form the Canadian Underwriters' Association. The depression had a major impact on the conduct of fire insurance, and the following editorial from the August 26, 1932, edition of the Insurance and Financial Chronicle prescribed some adjustments: Fire underwriting conditions have changed greatly during the past three years. The depression has taught prudence in the acceptance and the urgent necessity for scrupulously studying the effects of economic reverses and the increase of moral hazard. Responsible executives in home offices are bearing these facts in mind, but they have to depend upon their local agents for a knowledge of the character of the assured. a determination of the proper insurable value of property along with full details as to ownership and other vital considerations...Today the business is being selected with great caution, expenses are kept to a minimum, and losses are scrutinized most carefully.

Read more on Chapter 6

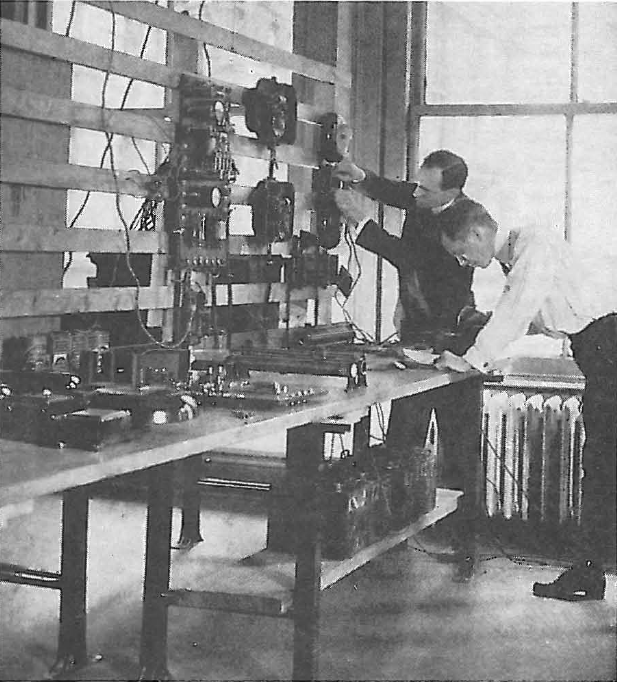

Insurance in a War Economy (1940-1950)

The war threw the world into chaos once again, and in the Canadian insurance industry, an immediate and increasing burden was placed on the Canadian Underwriters' Association. It was a time of challenge and the CUA responded by devoting much of its expertise to the war effort. The war brought about a shortage of staff, statistics of the past became useless, and lack of materials. The CUA also offered inspection of plants and other services for free to the government.

At all times, but particularly during the war, the Canadian Underwriters' Association stressed the need to reduce waste. CUA President K. Thorn called on fellow citizens to exercise care, stating that: The annual toll paid by insurance for fire losses and highway accidents is paid by the people of Canada by way of insurance premiums. Insurance premiums go into the cost of production of goods and the cost of services and thus are ultimately absorbed by the people as a whole. In these days of rapidly increasing taxation, in these times of salvage collection, and in a period when governments are going to extremes hitherto undreamed of to prevent inflation, it is not untimely to suggest that the Canadian public exercise a greater degree of care to reduce this terrific waste. (Monetary Times, January 1942.)

Read more on Chapter 7

Reconstruction and Expansion (1950-1960)

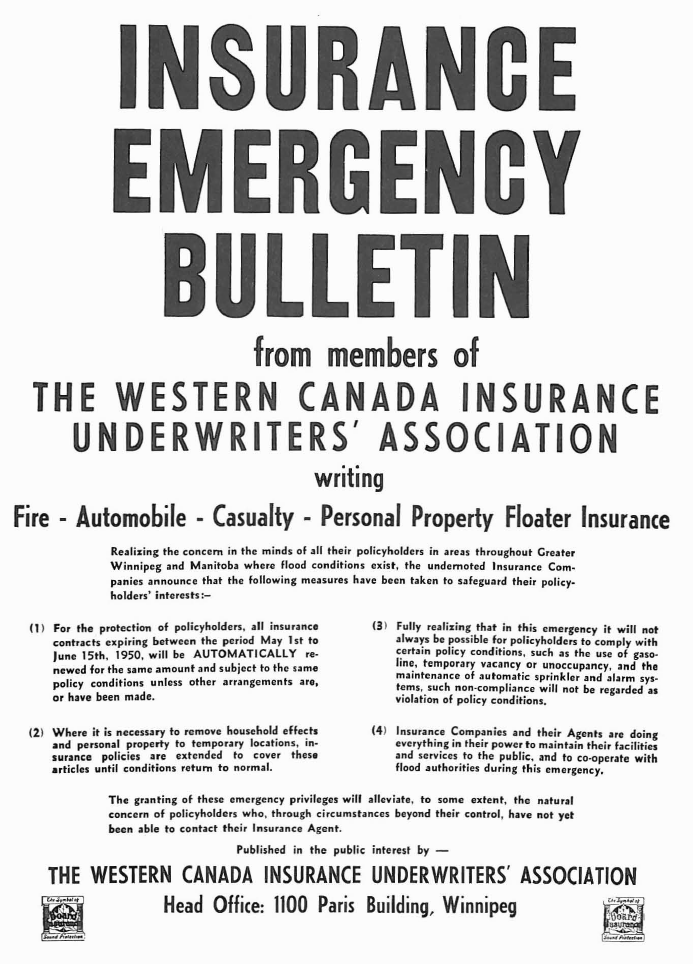

On May 7, 1950, fire broke out in the small Quebec town of Rimouski. It began in a lumber mill and was fanned by strong winds, causing some $20,000,000 worth of property damage, surpassing the 'Toronto fire of 1904 ($11 ,000,000). Before the Rimouski fire was brought under control, it had destroyed the seminary, convent hospital, court house, orphanage and seniors home. The fire had not yet been extinguished when company representatives met in Montreal to assess the extent of damage and to formulate plans to help the the thousands driven from their homes. William Perego (Royal) coordinated the efforts of the Canadian Underwriters' Association members and the Independent Fire Insurance Conference to create an emergency organization to handle the disaster. During this time, the rapid increase in the value of building materials and labour (costs had more than doubled between 1939 and 1948) many people still carried the same low insurance protection from the pre-war period. This was the major the issue that the CUA had to address in a recovering economy.

Read more on Chapter 8

The Struggle for Survival (1960-1970)

In 1961 and 1962, the return of profit was accompanied by renewed competition. The competition was so fierce that at times the existence of the Canadian Underwriters’ Association seemed threatened. Despite competition that forced lower rates and increased coverage, the CUA adapted to survive and merged from the market in a relatively strong position. In 1964, the CUA contributed in the formation of the Insurance Bureau of Canada. This Restored something of a sense of cooperation between insurance companies which, in turn, promoted a modest recovery in the latter half of the decade.

Read more on Chapter 9

A Fresh Start (1970-1980)

The 1970s began much as the last decade ended, with an unstable insurance market, relatively small underwriting losses and the future of the Canadian Underwriters' Association anything but clear. Due to underwriting losses of $140 million in 1973, the CUA was dissolved and replaced by the Insurers Advisory Organization of Canada in 1974. IAO’s purpose was to provide advice and information through benchmark rates, supporting statistical data, and other information. The CUA on contrast, used to be characterized by a rigid and rule based association.

During the decade, lAO suffered its share of disappointments as the quality of inspections, engineering and rating information did little to alleviate unfavourable underwriting results. Intense competition caused by a marked drop in the demand for insurance, a general slowdown in the Canadian economy and rapid inflation combined to produce a hectic and often confusing insurance market.

Read more on Chapter 10

The 1980s and Beyond

The first five years of lAO was a success and achieved its major objectives. Stability had returned to the industry and underwriting results did improve. It became clear that the organization would survive and prosper. But storm clouds had already begun to emerge on the horizon. Competition heated up, rate cutting again set in and underwriting results deteriorated. By the early 1980s it was as bad or worse than it ever had been and prices were being cut to the bone. Underwriting results took a nosedive. In 1980 the underwriting loss set a new record at $572 million, more than double the previous record of $283 million established in 1974. 1981 was a shocker. The underwriting loss climbed to $889 million. The only thing that was keeping the industry alive was its investment income. Clearly, corrective measures had to be taken but the insurers that tried to take the lead quickly found their business rapidly fleeing to other markets. Trying to come to grips with the economic upheaval of the early I980s was just one of lAO's major challenges of the new decade. There were many others that the organization - in what had become 'typical' fashion also tackled head on.

Read more on Chapter 11